No Rocket Regrets

Roger Clemens has not (yet) been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, but if it's salt in the wound, the former MLB pitcher doesn't seem to be pouting

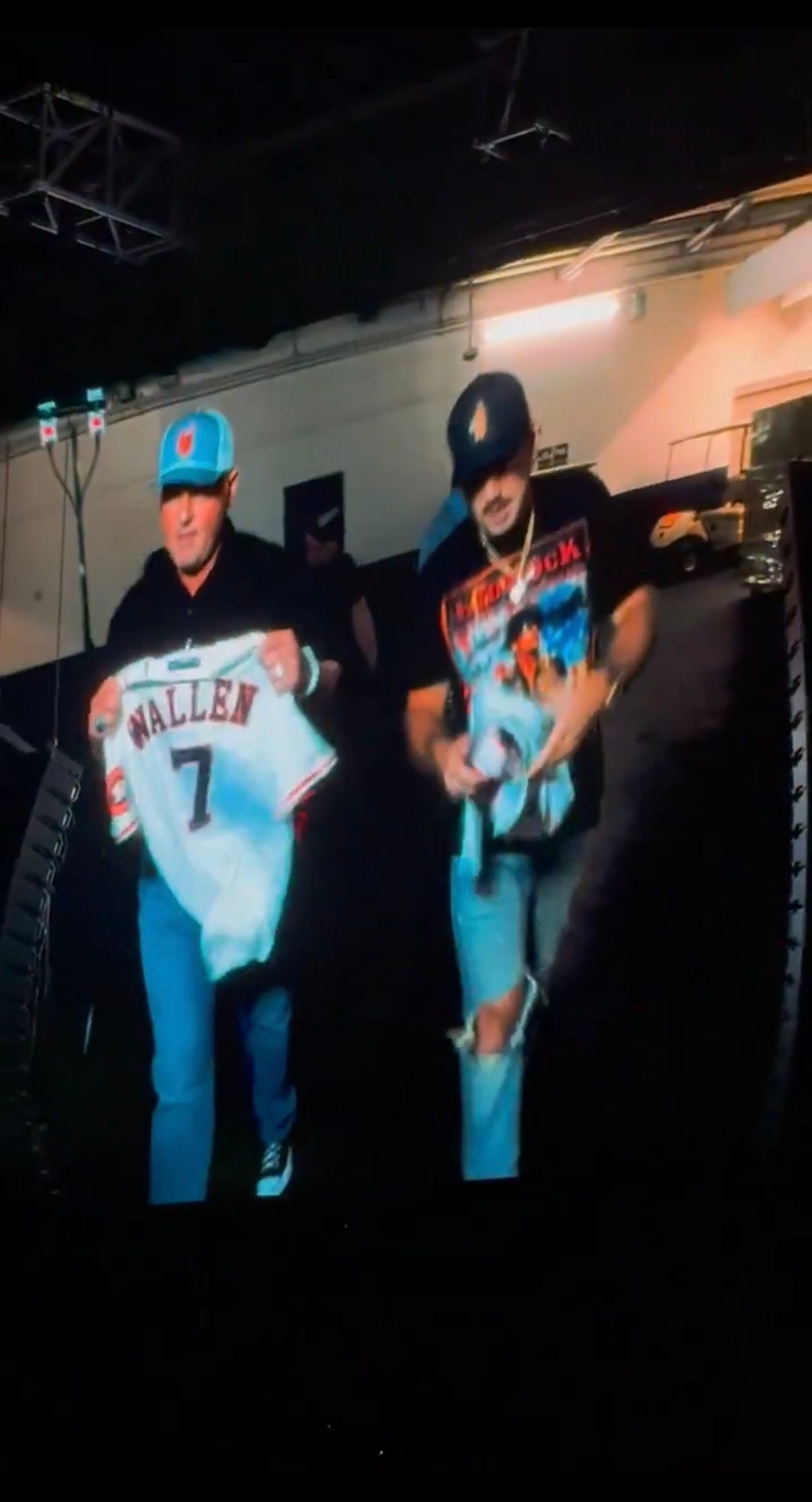

Country music star Morgan Wallen mugged for the cameras and strutted out of a tunnel at Houston’s NRG Stadium on a recent night of his “I’m the Problem” tour, while rapper Drake and Roger Clemens – yes, the steroid-stained, seven-time Cy Young Award-winning pitcher – provided backup support. Drake took a swig from a flask he was carrying, and the Rocket held up a No. 7 Astros jersey with “Wallen” stitched across the back as all three made their way toward the stage.

Clemens, 62, had already won three of those Cy Youngs and an American League MVP award before Wallen was even born, but the 30-year age gap didn’t stop the former MLB pitcher from stealing a little limelight from the country singer’s megawatt entrance. A Billboard story on Wallen referred to Clemens as a “baseball great,” and Houston is where the right-hander once played for the hometown Astros at the end of his career, from 2004-06.

A few days after the Wallen concert, Clemens took to X to express his appreciation for President Trump dropping an F-bomb when Trump addressed reporters about the unrest between Israel and Iran.

“Legend,” Clemens posted, and attached it to a separate post with a video clip of Trump’s profane remarks. (The post Clemens tagged was rife with typos, but hey, what’s a little grammar misfire these days?).

https://x.com/rogerclemens/status/1937522555511845018

And earlier this spring, Clemens made a cameo at the New York Yankees’ Tampa spring training complex after a lengthy exile from the club he pitched for from 1999-2003, and again in 2007. The exile stretched back to Clemens’ post-playing years, when he was consumed by the Mitchell Report fallout, an ensuing federal indictment, and the 2012 perjury and obstruction of Congress trial that ended with his acquittal on all counts.

Clemens also had a separate legal saga with his former trainer-turned-chief accuser, Brian McNamee, play out for years. Both men filed defamation lawsuits against each other – Clemens’ suit was eventually tossed, while McNamee reached a confidential settlement with Clemens’ insurer, AIG, in 2015.

But those personal and professional minefields seem to be far behind Clemens now, and perhaps the only proverbial thorn still firmly dug into Clemens’ side is his Cooperstown snub – from both the baseball writers and (so far) the HOF veterans committees.

If you’re going by Clemens’ public comments over the years, however, the 354-game winner does not seem to care that a plaque with his name doesn’t hang in the main hall at Cooperstown along with the other baseball greats, including one of his pitching idols, Nolan Ryan.

One such show of Clemens defiance occurred in early 2008, in his hometown Houston. Only a few months after the Mitchell Report on baseball’s doping history was released, and in which Clemens was named a steroid cheat, the Rocket went into full blitz damage control.

The report’s claims about Clemens’ past drug use were made by McNamee, who had told Mitchell and his investigators that he had personally injected the pitcher with steroids and human growth hormone during Clemens’ playing days in Toronto (1998) and with the Yankees (2000-01). Clemens immediately denied, denied, denied using PEDs, and issued a statement through his attorney – Houston-based Rusty Hardin – following the report’s release.

Then Clemens posted a pre-Christmas (2007) video on his own website with more denials.

Then Clemens agreed to an interview with “60 Minutes” veteran newsman Mike Wallace to attack the Mitchell Report claims.

Finally, Clemens and Hardin staged the Houston press conference a day after the “60 Minutes” segment, where a horde of over 40 credentialed media members, including me, gathered in a windowless room at the drab George R. Brown Convention Center.

After playing what became the infamous phone recording between Clemens and McNamee – the latter of whom was unaware he was being taped at the time of the phone call – Clemens entertained a brief Q&A. It was typical Clemens, who started off the press conference grumping about how he could not attend the funeral of the son of his college coach because he had to be at this press conference… a press conference which he had arranged.

During the Q&A, Clemens made a point to glare at certain reporters who had landed on his Nixon enemies list. It was the final question that sent Clemens into a particular fury.

How did he deal with people that already viewed him as guilty?

“I got another asinine question the other day about the Hall of Fame. You think that I played my career because I’m worried about the damn Hall of Fame? I could give a rat’s ass about that also. If you have a vote and it’s because of this, you keep your vote,” Clemens barked from a podium that day. “I don’t need the Hall of Fame to justify that I put my butt on the line and I worked my tail off. And I defy anybody to say I did it by cheating or taking any shortcuts.”

And with that, Clemens stormed off the dais and left Hardin to face the media mob.

Clemens huffing and puffing to blow whatever house down was something I’d seen less than a year earlier, in Lexington, Kentucky. A Daily News photographer and I were the sole recipients of Clemens’ wrath in that instance. Clemens, only days removed from announcing his comeback with the Yankees – his second stint in pinstripes – had begun training at the University of Kentucky along with the help of one Brian McNamee.

By the time I arrived at Kentucky’s baseball field with photographer Michael Appleton, Clemens had already addressed reporters the day before. We got access through the university’s athletic department rep, Scott Stricklin, and while we stationed ourselves on a platform beyond the center field fence, Clemens trained with McNamee and his son Koby (then playing for the Single-A Lexington Legends).

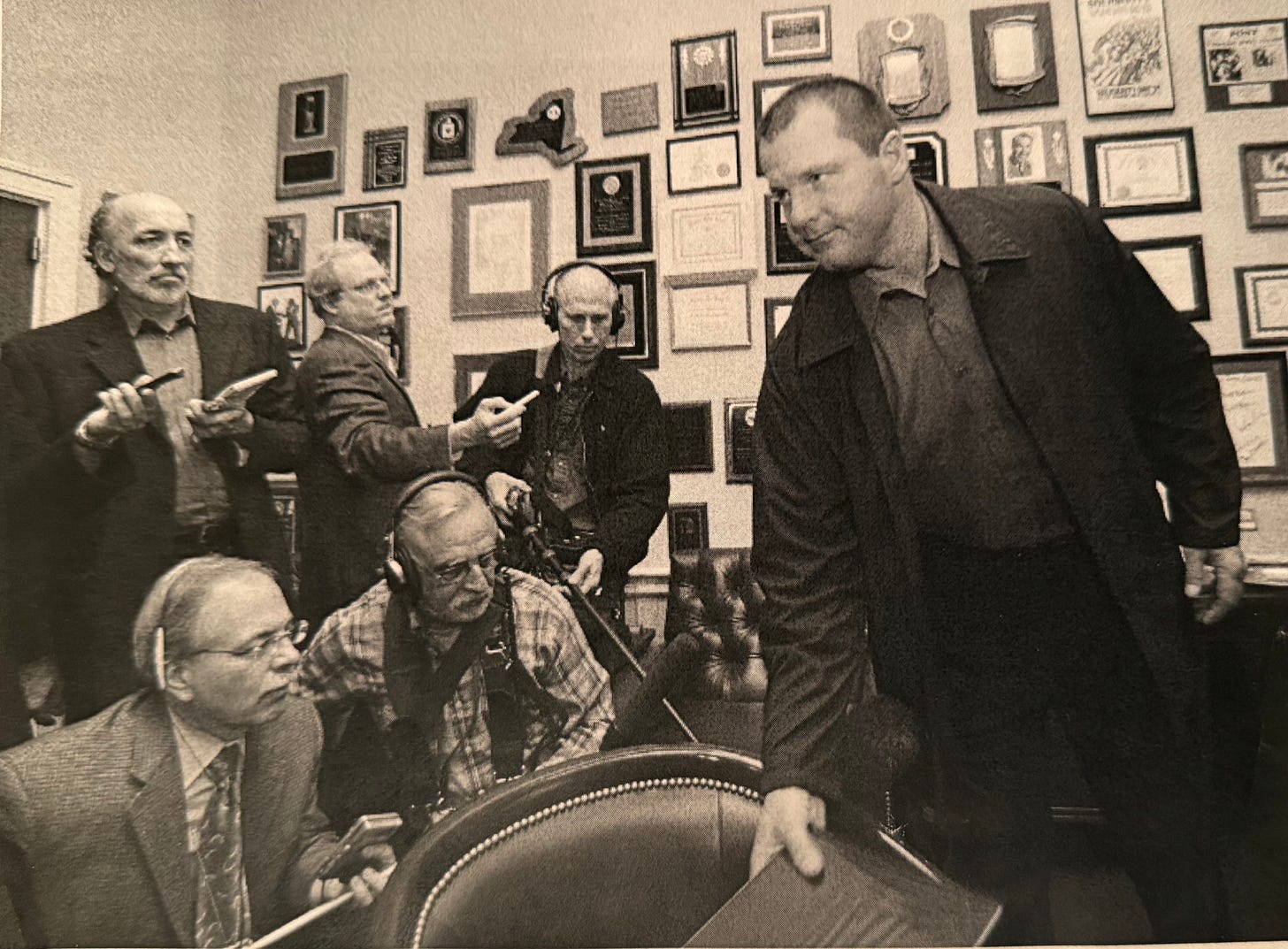

It didn’t take long for Clemens to get wind that a stray reporter and photog were there, and as I scrambled around to the front of the stadium to try and catch his exit after the workout had ended, unbeknownst to me, Clemens stormed toward Appleton in center field to “take some film,” his words, even though by 2007 photographers had been shooting digital for more than a decade.

The Appleton photo says it all.

(An unhappy Roger Clemens approaches former Daily News photographer Michael Appleton in 2007. Courtesy of Michael Appleton)

When he finally did appear out front, Clemens was all bark – “Where’s your cohort?!” he demanded of Appleton – and then dissed both of us for an ESPN crew. McNamee, meanwhile, stood close by, saying nothing.

Little did anyone know that later that day, McNamee would get a call from federal agent Jeff Novitzky, one of two federal authorities – the other being former AUSA Matt Parrella – who helped Mitchell compile his report. McNamee was at a Lexington Dick’s Sporting Goods store when Novitzky phoned, and needless to say, it wasn’t about sneaker sales.

McNamee was one of two key witnesses for Mitchell, and when he spoke with the former senator during the investigation, McNamee did so with the understanding that he “faced criminal jeopardy if he made any false statements,” as Mitchell stated in his report.

Fast forward to December of that year, days before the Mitchell Report release. I was dispatched into the winter night to try and interview McNamee at his Breezy Point home. It was a decidedly different stakeout than the “Steinbrenner Watch.”

Suffice to say, Breezy Point in early December, at night, trying to locate McNamee, was not an assignment for the meek. McNamee was a former NYPD cop and, later, an MLB strength coach with the Blue Jays and Yankees. He was most famously known as Clemens’ personal trainer. Still, doing a cold call door knock can always go sideways at any moment, whoever the target.

The Daily News I-Team had learned through our sources that McNamee had been interviewed by Mitchell and his investigators, and we were trying to get a jump on whose name might end up in the document. Clemens and his former Astros and Yankees teammate Andy Pettitte were the big names we had heard would be included.

I pulled into a parking lot near the address I had for McNamee and kept the heat running. Teri Thompson, the I-Team editor, and my colleague Michael O’Keeffe, were 3,000 miles away in San Francisco, doing some follow-up reporting on Barry Bonds’ federal indictment, which had occurred weeks earlier. Bonds, the recently-crowned home run king from that 2007 season, was likely to appear in the Mitchell Report as well, in connection with the still-churning BALCO case.

McNamee’s home looked dark from the outside, but I climbed a stairway and knocked. Then knocked some more. Nothing.

It would be several months before I would see McNamee in person, this time in Washington D.C. when he appeared before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Alongside Clemens.

It was Clemens who had been the lone bold face name to challenge Mitchell’s findings, and Congress decided to hold a hearing so the pitcher could air his grievances under oath.

“When it was all over, Clemens denied taking performance-enhancing drugs,” said Tom Davis, the former Republican chairman of the Oversight Committee, during a recent interview. “We (committee members) had said beforehand, ‘When you’re under oath, don’t screw around.’ It pained me to have to (later) refer Clemens to the Department of Justice.”

Before the DOJ referral, however, there was the lead up to the hearing.

Anyone in 2025 would find it hard to believe the lawyers who were assembled to represent both Clemens and McNamee. It was like the “Seinfeld” Bizarro World episode playing out in real life.

For McNamee, liberal-leaning Richard Emery and Earl Ward took the reins before Mark Paoletta came aboard. Paoletta, one of D.C.’s most influential Republican powerbrokers, serves as general counsel for the Office of Management and Budget in the Trump administration (and held the same position during Trump’s first term). Paoletta is also close friends with conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and he has represented Thomas’ wife, Ginni, in legal matters.

Paoletta had originally reached out to Hardin and Clemens to join forces with the pitcher’s defense team, but Paoletta never got a call back. Instead, he pivoted to Team McNamee.

For Clemens, Hardin was leading the charge, but Lanny Breuer soon joined Clemens’ army of attorneys. Breuer, the New York City-born attorney, was appointed Assistant Attorney General for the DOJ’s Criminal Division by President Barack Obama during Obama’s first term. He was also President Bill Clinton’s special counsel.

When Breuer came aboard Team Rocket in 2008, I reached him on the phone for an interview and he said one of his first orders of business was to “calm things down” in the Clemens camp – in other words, try to muzzle the sound bite-hungry Hardin.

The Friday before the Feb. 13, 2008 hearing, Clemens paraded around to different committee members’ D.C. offices, pressing flesh and trying to burnish his image and get in the good graces among the women and men he would appear before in a few days. It was a turbo-charged schedule, and Hardin and Breuer, as well as Clemens’ PR man, Joe Householder, were constantly in stride with their client.

I was in the media mix that Friday, a decidedly smaller group than previous days. It was not for the weary, keeping up a cardio workout pace while Clemens dashed from one office to the next, both in the Rayburn Building (where the hearing would be held) and the Cannon House Office Building. Two incidents involving Hardin stick out from that afternoon. I was able to see the garrulous Texas attorney at both his comedic and apoplectic best, starting with a moment of levity outside one of the elevator banks.

When Hardin saw me approaching for a comment, any comment, he got me in a mock headlock and gave me a noogie. “We will have no comment for the Daily News!” he joked while rapping his knuckles on my skull. He stepped into the elevator car with the Clemens posse and was still giggling when the doors closed and I was left on the outside looking in.

Hardin and Clemens’ whole legal team, with the exception of maybe Breuer, had taken issue with the Daily News coverage, but Hardin also was forever a showman, in and out of the courtroom, and knew how to play to the different media constituents.

(Roger Clemens (r.) before leaving Rep. Edolphus Towns’ office in February 2008, a few days before Clemens testified before the House Oversight Committee. I was in Towns’ office when this photo was taken, but got squeezed out of the frame. Photo courtesy of Reuters.)

One of the Rocket stops that afternoon was with Rep. Edolphus Towns, a New York Democrat who would later succeed Henry Waxman as chair of the Oversight Committee. In an unexpected break from the dizzying footrace to keep up with Clemens and Co., Towns invited a handful of reporters, including me, into his office after Clemens finished his visit.

Towns told us there was “none of that” in his meeting, meaning no autograph signings or fawning over the former major league pitcher. What Towns did find puzzling was the medical waste that McNamee had saved for years, and which allegedly contained Clemens’ DNA, and tied him to PED use. The News had broken the story on the medical paraphenalia.

“I mean, think about this – this guy (McNamee) has been walking around with this stuff for seven years. Doesn’t that seem a little strange?” Towns asked.

The afternoon faded into early evening, and just as Clemens was winding up his final meeting of the day with Rep. Paul Kanjorski, the Pennsylvania Democrat, the Daily News broke another story – this one about how McNamee said in his pre-hearing deposition that he had injected Clemens’ wife Debbie with human growth hormone in 2003, the year she posed for Sports Illustrated’s Swimsuit Issue, and that the injections had been done at Roger Clemens’ direction.

The media horde had grown considerably by the time Clemens emerged from Kanjorski’s office, and between the reporters jostling for position in the congressional hallways, Breuer blurting out, “Did Roger get the Cy Young because his wife took the HGH?”, and me having to ask Hardin to comment on our story, it was controlled chaos.

Hardin’s response to the DN report was a long way from his noogie he administered earlier.

“That it was at Roger’s direction? Let me repeat one more time – this guy (McNamee) is a colossal liar. And he has absolutely no shame,” said Hardin. He turned a deeper shade of purple when told the information the Daily News had been given was from a confidential source.

“Are you calling it a confidential source? I don’t respond to unnamed sources,” Hardin barked.

When the hearing finally commenced the following Wednesday, it was McNamee who appeared more calm and collected while he faced a blistering line of questioning from committee members. As the Daily News I-Team would later write in our 2009 book on Clemens and the sports steroid culture – “American Icon” – McNamee’s preparation before the hearing included Paoletta staging a “murder board,” or, a simulated hearing, at his law firm’s offices. Paoletta, Emery, Ward and Debbie Greenberger, another McNamee lawyer, took turns verbally accosting McNamee in a conference room in an effort to get him ready to face the congressional heat.

Even when committee members like Chris Shays (R - Conn.) called McNamee “a drug dealer” or Indiana Republican Dan Burton lambasted McNamee for keeping medical waste – “Are you lying about anything else? I mean, why don’t you tell us?” – McNamee kept his cool.

Clemens, meanwhile, used words like “misremembered” and even seemed resigned to his baseball legacy being forever mud when he said in his opening remarks: “I am never going to have my name restored, but I have got to try and set the record straight… Let me be clear – I have never taken steroids or HGH. Thank you.”

Congress thought otherwise, and ultimately the committee referred Clemens to the DOJ — accusing him of lying to Congress about his alleged PED use — which in turn launched a years-long investigation of the pitcher, one that ended with his 2010 indictment. Two years after that, Clemens’ federal trial ended with an acquittal on all perjury and obstruction counts. (McNamee was much more erratic on the stand during Clemens’ trial, perhaps a testament to not being put through another murder board simulation? Paoletta was not part of McNamee’s legal team during the trial).

My former colleague Mike O’Keeffe gave an insightful interview following the jury’s verdict, although the full scope and drama of the Clemens trial is deserving of a separate Substack post.

[https://www.pbs.org/video/pbs-newshour-roger-clemens-acquitted-but-legal-cloud-lingers/]

Clemens not only emerged unscathed from his federal trial, but his acquittal may have sparked a movement or public mindset that frowned upon professional athletes being prosecuted in connection to PED scandals. The judge in Clemens’ case declared a mistrial in 2011, and even though a second trial proceeded the following spring, the former U.S. Attorney for the Central District of California, André Birotte Jr., announced in early 2012 that his office was closing the federal investigation of cyclist Lance Armstrong, which centered on alleged criminal conduct tied to doping.

Novitzky had led that Armstrong investigation and told me in an interview years later that he was blindsided by Birotte’s announcement and that he never received any kind of explanation as to why that decision was made.

Both Novitzky and Parrella, the former federal prosecutor, told me for a 2020 Forbes story that Clemens and Bonds unequivocally used PEDs during their playing careers.

In that same story, I interviewed one of Clemens’ trial attorneys, Michael Attanasio, who gave the closest possible hint as to whether or not Clemens is bothered by his Hall snub. (Clemens was still on the writers’ ballot at that point).

“It disappoints me greatly. I don’t think it’s fair. I don’t think it’s right,” said Attanasio of Clemens’ Hall omission. “(Clemens) has made many comments about it — ‘That’s not why I played the game.’ He says, ‘Plenty of my stuff is already in (the Hall of Fame),’ referring to the 20-strikeout game, and stuff like that. So I take him at his word. But any player who gave what he gave to this game — I’m sure those are all true statements — but I’m also sure he would be greatly honored and humbled by it. I don’t think he’s waiting around for the call. I’m not going to cross wires with him on that. But how could anyone not be honored and humbled if the call ever comes?”

Could Clemens be behind the mic on the Hall of Fame dais one day in the future, giving his Cooperstown speech? That’s up to the veterans (Eras) committee now. Judging by his public appearances and social media posts, however, it doesn’t seem like Clemens is losing much sleep.